If we run linear regression in R, then we will see a term in the report “degrees of freedom” and that value equals n-p where n is the number of observations (data points) and p is the number of parameters (including intercept).

But what does it mean? How is it useful?

Short Answer: the degree of freedom represents the number of “free” or independent in the residuals from linear regression. The following three parts will explain this further.

1. Measure

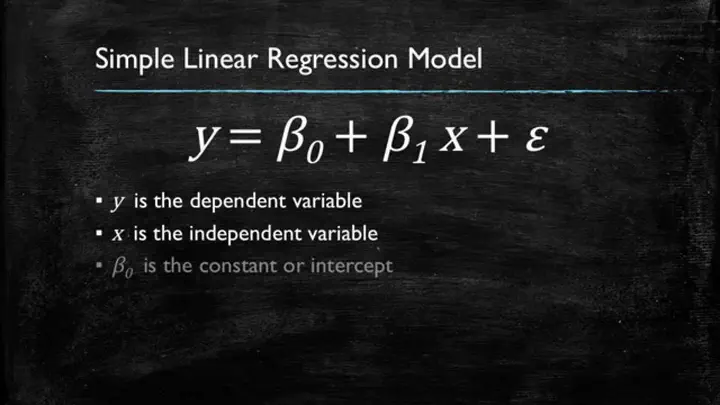

Under the Gauss-Markov model, which states where are iid errors centered at zero with variance . Here, and are all assumed determined. are the randomness here, which cause y to be random.

With the widely known formula, one can derive the BLUE estimator for and obtain estimated residual . Then, how can we estimate ? We have RSS, which is the residual sum of squares but what’s next?

A short answer is: . Here, the denominator is the degree of freedom. Proof follows from the fact that , where H is the projection matrix and error term centers at zero.

To make the proof easier, let us further assume error terms follow normality. Then, is similar to a chi-square distribution. Note, chi-square distribution with l degree of freedom means sum of l standard normal’s square.

But they are not identically the same. Actually, because the trace of (1-H) is n-p. This is because the eigenvalues of (1-H) is n-p and that is exactly the number of independent normal variables in the residual. so

2. Hypothesis Testing for

n-p is also the degree of freedom of t distribution for testing whether is zero. Note, t distribution . The n-p comes from the same chi-square distribution as we mentioned above.

But here, the assumption is that error term follows homoscedasticity. How do we estimate the standard error for under heteroscedasticity? It will be in the future posts about EHW and WLS.

3. Connection to 1-sample t-test

Let us first assume that we have shifted the Y with a null hypothesized mean for all i. Then, if the linear model is , which only includes the interception term, then , the sample average of Y. The RSS/(n-1) will be exactly the same as the sample variance of Y. We can notice that this is another reason for minus 1 in the denominator for computing sample variance. By part II, sample mean over sqrt of sample variance follows a t-distribution with df n-1.

4. Connection to 2-sample t-test

Let us assume that the linear model is , which includes the interception term and a binary variable X only takes 0 for 1. Moreover, X is 0 for control group and X is 1 for treatment group. We want to test whether the average treatment effect or diff-in-means significant enough. If we run the regression, the coefficient for X will be the diff-in-means estimator (difference between two sample mean). The standard error of beta will be the same as that of a 2-sample t-test if you algebraically solve for it by the equation above. Furthermore, the degree of freedom will be n-2 since p equal to 2 in this case.